Composers

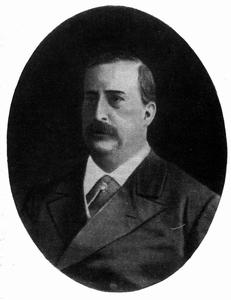

Alyabiev A. A.

Alexander Alexandrovich Alyabiev (1787 - 1851) is one of the best known Russian romantic composers of the first half of the XIX century. He is the author of popular in Russia every-day romances and songs ('The Nightingale'), as well as a number of chamber instrumental and theatre music pieces. He was the first Russian composer, who became acquainted with the musical folklore of the Bashkirs. A.A.Alyabiev was the first to introduce oriental themes and tunes into the Russian music.

The reason for the composer's close contacts with the musical culture of the peoples, inhabiting the Eastern end of the Russian Empire, was the dramatic events in his own life. Since he was considered an accessory to the political disturbances connected with the Decembrists movement in the middle of the 20-ies of the XIX century, the composer was arrested on a false accusation of crime. So by the mid of the 30-ies he was in an exile. On the one hand, these circumstances had widened his outlook, the theme and image diapason of his creative work, on the other, they negatively affected the fate of his compositions: most of his operas did not see the stage.

The areas of the composer's exile were the North Caucasus (1832-1833) and the Orenburg Gubernia (1833-1834), the present day Bashkortostan territory then being part of the latter. Alyabiev's accommodation was the Orenburg military garrison. From there he made trips to various parts of the region to be acquainted with the so strange to him, a European, life of the Asian people, inhabiting those places, such as the Bashkers, the Tartars, the Kazahs, the Kirguiz, the Turkmen. His impressions of the people and their life had enriched his ideas of the East and its musical culture in particular. Its monodic essence, improvisational character, the dominance of pentatonic scale, hexachord, seven step diatonic harmony structures seemed out of the ordinary to the Russian composer.

It was Alyabiev, who laid the foundations for folklore studies in Bashkortostan by collecting and deciphering music samples of Asian peoples. The best example of folk instrumental melodies arrangements (obviously, those played by the kurai) was a series of "Tartar Songs", that are referred to by the music researcher L.Atanova as belonging to Bashker ones. Another aspect of his attitude to Bashker music is obvious in the vocal series "Asian Songs" (1833-1835), in "The Bashkerian Overture", which was not completed, and in the opera "Ammalat-bek", where the composer either cites or creates themes according to folklore oriental style traditions. They show a recognition of common for the oriental monodic and European gamophone harmonic systems of thinking, regularities of musical themes and harmony tone developments. These peculiarities made it possible for Alyabiev to present the oriental ethnic musical material through the genres and forms of European music. Being a representative of the romanticist trend, the composer discovers a new type of dialogue between West and East, which was both typical for Europe and unexpectedly character specific. On the other hand, it was Alyabiev who showed the ways for correlation of the Russian European musical thinking system with that of Eastern Asiatic. This was the way for the creative activities of the Bashker composers to develop in the XX century.

Alyabiev's oriental works reproduce the romantic nature of the East. The composer was obviously attracted by the type of mentality of the oriental people, for the rational, the perceptual and the emotional was organically combined in their world perception. Those have been the result of their religious, social, cultural and historical traditions. Alexander Alexandrovich Alyabiev (1787 - 1851) is one of the best known Russian romantic composers of the first half of the XIX century. He is the author of popular in Russia every-day romances and songs ('The Nightingale'), as well as a number of chamber instrumental and theatre music pieces. He was the first Russian composer, who became acquainted with the musical folklore of the Bashkirs. A.A.Alyabiev was the first to introduce oriental themes and tunes into the Russian music.

The reason for the composer's close contacts with the musical culture of the peoples, inhabiting the Eastern end of the Russian Empire, was the dramatic events in his own life. Since he was considered an accessory to the political disturbances connected with the Decembrists movement in the middle of the 20-ies of the XIX century, the composer was arrested on a false accusation of crime. So by the mid of the 30-ies he was in an exile. On the one hand, these circumstances had widened his outlook, the theme and image diapason of his creative work, on the other, they negatively affected the fate of his compositions: most of his operas did not see the stage.

The areas of the composer's exile were the North Caucasus (1832-1833) and the Orenburg Gubernia (1833-1834), the present day Bashkortostan territory then being part of the latter. Alyabiev's accommodation was the Orenburg military garrison. From there he made trips to various parts of the region to be acquainted with the so strange to him, a European, life of the Asian people, inhabiting those places, such as the Bashkers, the Tartars, the Kazahs, the Kirguiz, the Turkmen. His impressions of the people and their life had enriched his ideas of the East and its musical culture in particular. Its monodic essence, improvisational character, the dominance of pentatonic scale, hexachord, seven step diatonic harmony structures seemed out of the ordinary to the Russian composer.

It was Alyabiev, who laid the foundations for folklore studies in Bashkortostan by collecting and deciphering music samples of Asian peoples. The best example of folk instrumental melodies arrangements (obviously, those played by the kurai) was a series of "Tartar Songs", that are referred to by the music researcher L.Atanova as belonging to Bashker ones. Another aspect of his attitude to Bashker music is obvious in the vocal series "Asian Songs" (1833-1835), in "The Bashkerian Overture", which was not completed, and in the opera "Ammalat-bek", where the composer either cites or creates themes according to folklore oriental style traditions. They show a recognition of common for the oriental monodic and European gamophone harmonic systems of thinking, regularities of musical themes and harmony tone developments. These peculiarities made it possible for Alyabiev to present the oriental ethnic musical material through the genres and forms of European music. Being a representative of the romanticist trend, the composer discovers a new type of dialogue between West and East, which was both typical for Europe and unexpectedly character specific. On the other hand, it was Alyabiev who showed the ways for correlation of the Russian European musical thinking system with that of Eastern Asiatic. This was the way for the creative activities of the Bashker composers to develop in the XX century.

Alyabiev's oriental works reproduce the romantic nature of the East. The composer was obviously attracted by the type of mentality of the oriental people, for the rational, the perceptual and the emotional was organically combined in their world perception. Those have been the result of their religious, social, cultural and historical traditions.

The leading spheres of his oriental compositions are lyrical, mode of life genre and religious. Their main theme is love. One of the leading beliefs of romantic art is the impossibility of happiness in real life, which appeared to closely correlate with that of oriental understanding. A poignant delight of suffering, a cult of an imminent tragedy of love has become common practice there. The heroes do not seek any redemption of suffering, do not strife for a re-union with the loved ones, even if they do, their attempts are either futile or tragically doomed. That theme is heard in two of the Bashker songs of the vocal series the "Asian Songs" (the lyrics/text author is unknown) and the opera "Ammalat-bek" concept. Both the songs "I'll Stroll through the Bridge" and "Between the Granite Cliffs" tell of dramatic lyrical sufferings of the hero and his beloved, who had lost any hope of seeing him again. The poetic text of the songs (which is written in the oriental folklore style) contains images of nature (rough, boiling sea, idyllic pictures of spring, trees in bloom), which serve as resonators amplifying the heroes feelings (of the girl) and opposing them to deceitful idyllic lure (the young man). This kind of nature image's treatment is typical of both romanticism and folklore. Scenes of nature take a particular place in the Bashker folk poetic creative activities, which is connected with pantheistic, pagan assumptions of the people, who animated in their beliefs forces of nature (the mono-dialogue of the girl with the sea) and fauna representatives (a raven as a symbol of death in Alyabiev's song).

The concept of the "Ammalat-bek" opera (1847), written after A.Bestuzhev-Marlinski, libretto by A.Veltman, is tragic. It tells about the events of the Caucasian War, in which the composer himself participated. Alyabiev compared the proximity of both cultural and historic traditions of the Moslem peoples. He managed to hear and reproduce what was in common in the musical style of both the Bashkerian and the Caucasian musical folklore.

Meditation, passiveness, an esthetic delight in suffering are the features typical of the oriental world perception, which predetermine the heroes behavior. Ammalat and Sultanetta are suffering doomed lovers unable to change the dramatic fatality of the situation and take a different approach to the immoral demands of Ahmet-han, the girl's father. The latter is guided by pragmaticism and political expediency. In spite of the sufferings of his daughter, which he is aware of, he is pursuing his own aim. The opera is written in the genre of romantic fatal drama, which was popular in West European music of the 30-ies and 40-ies of the XIX century.

Islam is the personification of the eternal stable law of life in the opera (the mullah's prayer sounds at the acme of the action). It predetermines the events, supporting the eternal character of their essence. The religious, mystical and historical, political scope is focussed on the idea of jihad (the struggle of man with the negative spheres, personified in the image of Iblis-Satan, which involves the idea of struggle against the faithless). The character of Ammalat-bek, his moral and psychological struggle in the midst of Ahmet-khan political interests and love for Sultanetta, the feeling of friendship and duty to the Russian Colonel, who had been defamed by the khan, disclose the above principles in a feature form. The bek's foster-brother Alie regards Ammalat as the one in the possession of demonic forces, and is trying to save him from the moral collapse, but in vain.

Borodin A. P.

Alexander Porphirievich Borodin was born in 1833 in Georgia, the illegitimate son of a serf and a Georgian prince. His mother later married a retired doctor, and Alexander was brought up in St. Petersburg with a good education. He got into the Academy of Medicine in St. Petersburg in 1850 where he studied to become a scientist. From 1864 until his death in 1887, he was a professor of chemistry at the St. Petersburg Military Academy; he both taught and did research. He worked hard to establish a medical school for women in Russia. Women were not admitted to the Academy, although there was some relaxation of the restrictions during the more liberal 1860's. Borodin's laboratory became the first place women were legally allowed to study medicine, but the right was eventually revoked by order of the repressive regime of Tsar Alexander III. Alexander Porphirievich Borodin was born in 1833 in Georgia, the illegitimate son of a serf and a Georgian prince. His mother later married a retired doctor, and Alexander was brought up in St. Petersburg with a good education. He got into the Academy of Medicine in St. Petersburg in 1850 where he studied to become a scientist. From 1864 until his death in 1887, he was a professor of chemistry at the St. Petersburg Military Academy; he both taught and did research. He worked hard to establish a medical school for women in Russia. Women were not admitted to the Academy, although there was some relaxation of the restrictions during the more liberal 1860's. Borodin's laboratory became the first place women were legally allowed to study medicine, but the right was eventually revoked by order of the repressive regime of Tsar Alexander III.

Borodin dropped dead of a stroke at a party in 1887.

He showed an early interest in music, and from a young age played the flute and piano. He wrote a piano duet at the age of nine. After graduation from the Medical Academy, he fell under the influence of the Russian composer Mily Balakirev and studied composition with him. Balakirev, Bodorin, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Cesar Cui, and Modest Mussorgsky became known as the Mighty Five or the Mighty Bunch in St. Petersburg cultural circles in the 1860's. They started the Free Music Academy, advocating music education for everyone, in opposition to the "official" Academy of Music in St. Petersburg, founded by Anton Rubenstein and supported by the imperial government. As nationalism swept across the European continent and elsewhere, the Mighty Five, along with artists and musicians all over Russia, wanted to create art and music that was distinctly Russian, turning away from the influences of western Europe. While many composers at the time, like Chaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, drew on Russian folk melodies for inspiration, Borodin did not; but he related his music to images of Russian places and themes.

His friend Nikolai Rimsky-Korsokov said about Borodin: "Borodin was an exceedingly cordial and cultured man, pleasant and oddly witty to talk with. On visiting him I often found him working in the laboratory which adjoined his apartment. When he sat over his retorts filled with some colourless gas and distilled it by means of a tube from one vessel into another, Iused to tell him that he was transfusing emptiness into vacancy."(2)

Most composers in St. Petersburg did not make their primary living composing, and in this tradition, Borodin kept his job at the St. Petersburg Military Academy, even after he began composing a lot of music. His first symphony was written during the years 1862-1867 and performed in 1869; his second symphony took from 1869-1876; and his third symphony, begun in 1882, was not completed before he died. He never had the time to compose that he wanted to have. Besides his symphonies, he wrote piano music, short works like "In the Steppes of Central Asia" recalling the country of his birth, and a major opera, Prince Igor, which was also unfinished at the time of his death. Rimsky-Korsakov and one of his students, Alexander Glazunof, finished Prince Igor; Glazunof alone finished the two existing movements of Borodin's third symphony from notes left by Borodin.

The sound clip below is from the second movement of the Third Symphony, which uses many different rhythms and key shifts, and features quick movement between major and minor keys.

Long after Borodin's death in 1887, his music was used for a Broadway show, Kismet. Kismet had been a play, written in 1911, and had been made into a movie twice. Charles Lederer and Luther Davis adapted it for Broadway, and Borodin's music was reworked by Robert Wright and George Forrest to fit the story of a poet-thief who becomes the Emir of Baghdad in a magical day. The two clips below are an example of Borodin's original work and the same music in its Broadway rendition. The original comes from the fourth movement of his first symphony. The song from Kismet is entitled "Gesticulate."

The best known melody of Borodin's was also used in Kismet, where it was the major popular hit song from 1953, "Stranger in Paradise," popularized by Tony Bennett. It came from the Polovtsian Dances, which were orchestral pieces in Borodin's opera Prince Igor. The dances, like much of Borodin's other work, have a noticeable Asian flavor to them. The sound clip below is the first appearance of this musical theme in the 8th Polovtsian dance.

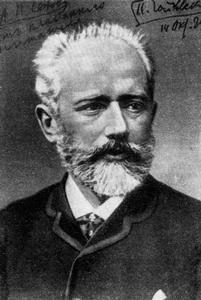

Chaikovsky P. I.

Peter Iliych Chaikovsky (1840-1893), Russian composer, the foremost of the 19th century. Chaikovsky was born in Votkinsk, in the western Ural area of the country. He studied law in Saint Petersburg and took music classes at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. There his teachers included Russian composer and pianist Anton Rubinstein, from whom Chaikovsky subsequently took advanced instruction in orchestration. In 1866 composer-pianist Nikolai Rubinstein, Anton's brother, obtained for Chaikovsky the post of teacher of harmony at the Moscow Conservatory. There the young composer met dramatist Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky, who wrote the libretto for Chaikovsky's first opera, The Voyevoda (1868). From this period also date his operas Undine (1869) and The Oprichnik (1872); the Piano Concerto no. 1 in B-flat Minor (1875); the symphonies no. 1 (called "Winter Dreams," 1868), no. 2 (1873; subsequently revised and titled "Little Russian"), and no. 3 (1875); and the overture Romeo and Juliet (1870; revised in 1870 and 1880). The B-flat piano concerto was dedicated originally to Nikolai Rubinstein, who pronounced it unplayable. Deeply injured, Chaikovsky made extensive alterations in the work and reinscribed it to German pianist Hans Guido von Blow, who rewarded the courtesy by performing the concerto on the occasion of his first concert tour of the United States (1875-1876). Rubinstein later acknowledged the merit of the revised composition and made it a part of his own repertoire. Well known for its dramatic first movement and skillful use of folklike melodies, it subsequently became one of the most frequently played of all piano concertos. In 1876 Chaikovsky became acquainted with Madam Nadejda von Meck, a wealthy widow, whose enthusiasm for the composer's music led her to give him an annual allowance. Fourteen years later, however, Madame von Meck, believing herself financially ruined, abruptly terminated the subsidy. Although Chaikovsky's other sources of income were by then adequate to sustain him, he was wounded by the sudden defection of his patron without apparent cause, and he never forgave her. The period of his connection with Madame von Meck was one of rich productivity for Chaikovsky. To this time belong the operas Eugene Onegin (1878), The Maid of Orleans (1879), Mazeppa (1883), and The Sorceress (1887); the ballets Swan Lake (1876) and The Sleeping Beauty (1889); the Rococo Variations for Cello and Orchestra (1876) and the Violin Concerto in D Major (1878); the orchestral works Marche Slave (1876), Francesca da Rimini (1876), Symphony no. 4 in F Minor (1877), the overture The Year 1812 (1880), Capriccio Italien (1880), Serenade (1880), Manfred symphony (1885), Symphony no. 5 in E Minor (1888), the fantasy overture Hamlet (1885); and numerous songs. Meanwhile, in 1877, Chaikovsky had married Antonina Milyukova, a music student at the Moscow Conservatory who had written to the composer declaring her love for him. The marriage was unhappy from the outset, and the couple soon separated. From 1887 to 1891 Chaikovsky made several highly successful concert tours, conducting his own works before large, enthusiastic audiences in the major cities of Europe and the United States. He composed one of his finest operas, The Queen of Spades, in 1890. Early in 1893 the composer began work on his Symphony no. 6 in B Minor, subsequently titled Pathetique by his brother Modeste. The first performance of the work, given at St. Petersburg on October 28, 1893, under the composer's direction, was indifferently received. Chaikovsky died nine days later. Peter Iliych Chaikovsky (1840-1893), Russian composer, the foremost of the 19th century. Chaikovsky was born in Votkinsk, in the western Ural area of the country. He studied law in Saint Petersburg and took music classes at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. There his teachers included Russian composer and pianist Anton Rubinstein, from whom Chaikovsky subsequently took advanced instruction in orchestration. In 1866 composer-pianist Nikolai Rubinstein, Anton's brother, obtained for Chaikovsky the post of teacher of harmony at the Moscow Conservatory. There the young composer met dramatist Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky, who wrote the libretto for Chaikovsky's first opera, The Voyevoda (1868). From this period also date his operas Undine (1869) and The Oprichnik (1872); the Piano Concerto no. 1 in B-flat Minor (1875); the symphonies no. 1 (called "Winter Dreams," 1868), no. 2 (1873; subsequently revised and titled "Little Russian"), and no. 3 (1875); and the overture Romeo and Juliet (1870; revised in 1870 and 1880). The B-flat piano concerto was dedicated originally to Nikolai Rubinstein, who pronounced it unplayable. Deeply injured, Chaikovsky made extensive alterations in the work and reinscribed it to German pianist Hans Guido von Blow, who rewarded the courtesy by performing the concerto on the occasion of his first concert tour of the United States (1875-1876). Rubinstein later acknowledged the merit of the revised composition and made it a part of his own repertoire. Well known for its dramatic first movement and skillful use of folklike melodies, it subsequently became one of the most frequently played of all piano concertos. In 1876 Chaikovsky became acquainted with Madam Nadejda von Meck, a wealthy widow, whose enthusiasm for the composer's music led her to give him an annual allowance. Fourteen years later, however, Madame von Meck, believing herself financially ruined, abruptly terminated the subsidy. Although Chaikovsky's other sources of income were by then adequate to sustain him, he was wounded by the sudden defection of his patron without apparent cause, and he never forgave her. The period of his connection with Madame von Meck was one of rich productivity for Chaikovsky. To this time belong the operas Eugene Onegin (1878), The Maid of Orleans (1879), Mazeppa (1883), and The Sorceress (1887); the ballets Swan Lake (1876) and The Sleeping Beauty (1889); the Rococo Variations for Cello and Orchestra (1876) and the Violin Concerto in D Major (1878); the orchestral works Marche Slave (1876), Francesca da Rimini (1876), Symphony no. 4 in F Minor (1877), the overture The Year 1812 (1880), Capriccio Italien (1880), Serenade (1880), Manfred symphony (1885), Symphony no. 5 in E Minor (1888), the fantasy overture Hamlet (1885); and numerous songs. Meanwhile, in 1877, Chaikovsky had married Antonina Milyukova, a music student at the Moscow Conservatory who had written to the composer declaring her love for him. The marriage was unhappy from the outset, and the couple soon separated. From 1887 to 1891 Chaikovsky made several highly successful concert tours, conducting his own works before large, enthusiastic audiences in the major cities of Europe and the United States. He composed one of his finest operas, The Queen of Spades, in 1890. Early in 1893 the composer began work on his Symphony no. 6 in B Minor, subsequently titled Pathetique by his brother Modeste. The first performance of the work, given at St. Petersburg on October 28, 1893, under the composer's direction, was indifferently received. Chaikovsky died nine days later.

Many Chaikovsky compositions-among them The Nutcracker (ballet and suite, 1891-1892), the Piano Concerto no. 2 in G Major (1880), the String Quartet no. 3 in E-flat Minor (1876), and the Trio in A Minor for Violin, Cello, and Piano (1882)-have remained popular with concertgoers. His most popular works are characterized by richly melodic passages in which sections suggestive of profound melancholy frequently alternate with dancelike movements derived from folk music. Like his contemporary, Russian composer Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, Chaikovsky was an exceptionally gifted orchestrator; his ballet scores in particular contain many striking effects of orchestral coloration. His symphonic works, popular for their melodic content, are also strong (and often unappreciated) in their abstract thematic development. In his best operas, such as Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades, he used highly suggestive melodic passages to depict a dramatic situation concisely and with poignant effect. His ballets, notably Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty, have never been surpassed for their melodic intensity and instrumental brilliance. Composed in close collaboration with choreographer Marius Petipa, they represent virtually the first use of serious dramatic music for the dance since the operatic ballet of German composer Christoph Willibald Gluck. Chaikovsky also extended the range of the symphonic poem, and his works in this genre, including Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet, are notable for their richly melodic evocation of the moods of the literary works on which they are based.

Dargomyzhsky A. S.

Alexander Sergeyevich Dargomyzhsky (1813 - 1869) was a Russian nationalist composer best known for his operas. Dargomyzhsky's only musical education was provided by a set of exercise books lent to him by Mikhail Glinka, whom he met in 1833. Dargomyzhsky's first opera, Esmeralda (1839), is basically French in character, but with Rusalka (1856) he showed a marked gift for re-creating specifically Russian characters, scenes, and speech rhythms. His most important work is a word-by-word setting of Aleksandr Pushkin's play The Stone Guest (first performed posthumously in 1872), which consists almost entirely of a type of recitative and short lyrical passages. In this opera Dargomyzhsky reproduced with striking accuracy not only the rhythms but the stresses and pitches of Russian speech, exercising a strong influence on Modest Mussorgsky and later Russian composers. He also wrote songs of lasting value. Alexander Sergeyevich Dargomyzhsky (1813 - 1869) was a Russian nationalist composer best known for his operas. Dargomyzhsky's only musical education was provided by a set of exercise books lent to him by Mikhail Glinka, whom he met in 1833. Dargomyzhsky's first opera, Esmeralda (1839), is basically French in character, but with Rusalka (1856) he showed a marked gift for re-creating specifically Russian characters, scenes, and speech rhythms. His most important work is a word-by-word setting of Aleksandr Pushkin's play The Stone Guest (first performed posthumously in 1872), which consists almost entirely of a type of recitative and short lyrical passages. In this opera Dargomyzhsky reproduced with striking accuracy not only the rhythms but the stresses and pitches of Russian speech, exercising a strong influence on Modest Mussorgsky and later Russian composers. He also wrote songs of lasting value.

Glazunov A. K.

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov (1865 - 1936) was a true Russian Romantic who lived through the first of Russia's great upheavals in the 20th century. He quickly fell out of fashion while a younger generation of composers he had helped to nurture - among them Prokofiev and Shostakovich - came to prominence. Yet now we value his beautifully finished, well-proportioned symphonies, divorced from the times in which they were written. He was certainly not a composer who pushed forward the boundaries of musical knowledge, but the undeniable robustness and sense of well-being behind so many of his earlier works still endears them to listeners.

For the first half of his life, at least, Glazunov seemed born under a lucky star. The child of prosperous parents - his father was a book publisher - he showed strong musical talents from the start, but his compositional skill took wing in his early teens when Rimsky-Korsakov took him on as a private pupil. The older composers described his progress in his memoirs as "hourly, not daily", and memorably described the first performance of the 16-year-old Glazunov's First Symphony on March 29, 1882: "the audience was astonished when the composer stepped forward dressed in his college uniform in response to calls for him". A crucial sponsor at this time was that generous patron of the arts Mitrofan Belyayev, who undertook to publish his new compositions and in 1884 took him on a trip to western Europe, where he met Liszt in Weimar. The circle of composers and performers gathered around their patron, which became known as the "Belyayev Circle", took the cause of Russian music one step further, and Glazunov was very much its young lion.

In addition to his valuable work on the completion of Borodin's Prince Igor following Borodin's death in 1887, Glazunov continued to pursue the symphonic line, and following a brief creative crisis in 1890-1, produced three symphonies that decade which reflect his wholesome, cheerful and fundamentally conservative outlook. The Fourth weaves its thematic material together skilfully in a three-movement form full of fantasy; its successors are experiments in the grand style tempered by sequences of great individuality. He also showed his skill as Tchaikovsky's natural successor with the ballet scores Raymonda (1896) and The Seasons (1899). As a conductor he was less assured, and legend has ascribed him a certain notoriety at the premiere of Rachmaninov's First Symphony in 1897 when his poor (and allegedly drunken) handling of the orchestra contributed to the work's disastrous reception.

In 1899, Glazunov was appointed professor at the St Petersburg Conservatory, resigning in 1905 as part of a widespread protest; the students had gone on strike in sympathy with the victims of the January massacre in Palace Square, director Rimsky-Korsakov had shown his solidarity for them and had promptly been dismissed by the government authorities. At the end of the year, the liberals' demands were met and Glazunov returned to work - this time as the elected Director of the Conservatory, a post he retained for the next quarter of a century.

As he stood his ground on behalf of the institution throughout the upheavals of 1917 and its aftermath, Glazunov's creative output dwindled. The Eighth Symphony of 1906 was the last he completed, and although his later works include such piquant oddities as the Concerto for Coloratura Soprano and Orchestra, his music was now considered an irrelevance, and he produced nothing of major stature. Shostakovich was among the grateful students at the Conservatory to recall his unstinting support during the uncertainties of the 1920s. The pressures of dealing with the Soviet regime, however, took their toll. After a number of extensive foreign tours he settled in Paris in 1932 with the wife he had so unexpectedly married a few years earlier, and died there in 1936. One of his last and most unexpected legacies was a recording of The Seasons he made in London in 1929; it has a spirit and precision that do much to redeem his infamous reputation as a conductor.

Key Dates

1865 Born 10 August in St Petersburg

1882 Hears his First Symphony performed for the first time, conducted by Balakirev

1885 Wealthy patron Mitrofan Belyayev takes him on a tour of western Europe

1891 Overcomes creative crisis to produce many of his finest works

1899 Appointed Professor of St Petersburg Conservatory

1905 Resigns conservatory post in solidarity with Rimsky-Korsakov; takes up Directorship at end of year

1922 Named People's Artist of the Soviet Republic

1928 Leaves the Soviet Union for the first of many extended trips to the west

1932 Settles in Paris

1936 Dies at Neuilly-sr-Seine, 21 March

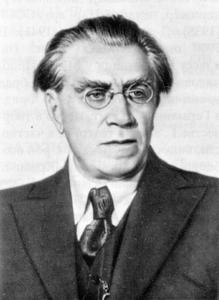

Glier R. M.

Reinhold Moritsevich Glier Reinhold Moritsevich Glier

Glier - composer, conductor, teacher. The national actor of the USSR (1938).

Born January 11, 1875 in Kiev. Died June 23, 1956 in Moscow.

Glier studied at the Moscow Conservatory until 1900 with Hrimaly for the violin, Taneyev, Arensky, Konyus and Ippolitov-Ivanov for theory and composition.

From 1920 -1941 was a professor of composition at the conservatory, where his pupils included Davidenko, Novikov, & Rakov among others.

Glier was also chairman of the USSR Composers' Union (1938-1948). He received several State Prizes (1942,1946,1948,1950) and held the title of People's Artist of the USSR in 1938, the RSFSR, the Uzbek SSR and the Azerbaijani SSR.

His students included A. and B. Aleksandrov, Bagrinovsky, Bruk, Bugoslavsky, Davidenko, Fere, Frolov, N. Golubev, Gozenpud, Gunst, A. Khachaturian, Klyucharyov, Knipper, Liatoshinsky, Miaskovsky, Prokofiev, Rakov and many others.

His most popular works include "The Red Poppy" and "The Bronze Horseman". His Harp Concerto is among the finest concertos for this instrument.

Glier was a direct heir to the Russian Romantic tradition, working on a grand scale in the large forms (opera, ballet, symphony, and symphonic poem). He formed a link between the Tchaikovsky/Taneyev scholl and the next generation of Russian/Soviet composers, including Prokofiev, Miaskovsky and A. Khachaturian.

His symphonic works draw on the Russian tradition of Borodin and Glazunov. This is especially clear in his Third Symphony 'Il'ya Muroments', named after a Russian folk hero, but all his symphonies, concertos and symphonic poems show a monumentality of image and a brilliant aural imagination.

His interest in the music of the Ukrainians and in Eastern music led him to write stage works based on the folk culture of the Soviet republics of the Transcaucasus and Central Asisa; in this he was a pioneer. His works in this regard stimulated the development of professional music in the eastern republics.

Glinka M. I.

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (1804 - 1857) in village Novospasskoe, Smolenskaya oblast. Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (1804 - 1857) in village Novospasskoe, Smolenskaya oblast.

Not for nothing was he dubbbed 'the father of Russian music'. Just as the poet Alexander Pushkin raised to a new level of perfection the poetic Russian of his elders, so Glinka - Pushkin's contemporary - fused lessons learnt abroad with a native inflection barely detectable in the previous generation of composers. His influence on the next generation of composers, like that of all founding fathers, was perhaps disproportionate to the modest genius of his music, but his uncanny instinct for the right orchestral colours and his well-proportioned tunefulness were good role models for Chaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and others.

The story of Glinka's early years reveals a pattern to be repeated in the case of several other great Russian composers. The son of wealthy parents with an estate in the Smolensk district, he came to know his music through the rich folk tradition of the family servants; he played violin and piccolo alongside the serfs in his uncle's orchestra. He also enjoyed a few lessons with the famous pianist John Field, pioneer of the Nocturne. In 1824 he entered the Ministry of Communications in St. Petersburg, thus setting the familiar Russian example of the composer as a pen-pusher dabbling in music in his spare time. Six years later, he enjoyed a sense of release by travelling to Italy, where he studied rather half-heartedly in Milan and met the reigning operatic masters Donizetti and Bellini; much of his music from this period shows an Italianate, bel canto flair. His real training took place in Berlin where, at the age of 29 he at last acquired some thorough working knowledge of harmony and counterpoint.

Glinka's years in the west finally led him to one conclusion: that the musical airs of his homeland were utterly different in inflection and general characteristics to the western forms which had held him spellbound for so long, and he determined to do otherwise. For his first major opera he turned to a theme which had been already been set to music by a Petersburg-based Italian composer, Caterino Cavos, two decades earlier: the sacrifice made by a simple Russian peasant, Ivan Susanin, to save the first Romanov tsar from a Polish invasion. Glinka's A Life for the Tsar opened in St Petersburg on December 9 1836 - a momentous date in Russian musical history. While there are still traces of Italian operatic style in many of the arias and ensembles, a new note enters Russian music in the authentic peasant choruses and above all in the powerful final lament of the self-sacrificing Susanin - a model for Russian operatic heroes to come.

Glinka's second opera, Ruslan and Lyudmila, takes several steps forward in the exotic orchestral means engaged by the composer to depict the supernatural subject-matter. A dramatically cumbersome adaptation of Pushkin's early verse tale, it is also the first of many great Russian operas to set the 'father of Russian literature' to music. Pushkin himself was killed in a duel before he could help Glinka with the libretto.

The mixed reception of Ruslan and Lyudmila at its 1842 premiere discouraged Glinka from pursuing his operatic quest, and the works of his final years tended to be on a smaller scale. Tchaikovsky later said of one of them, Kamarinskaya, a skilful and jolly fusion of two folk tunes, that all Russian symphonic music was in it 'as the oak is in the acorn'. Much of his time was taken up with further foreign tours; Berlioz welcomed him in Paris, and a trip to Spain fired his enthusiasm for Spanish music, resulting in the Capriccio brillante on the Jota Aragonesa and Night in Madrid. One of his last enthusiasms was for the music of the Italian Renaissance, which he studied in the hope of revitalising Russian church music, but further lessons with Dehn in Berlin were cut short by a cold which hastened his death in February 1857.

Grigorovich Yu. N.

Yury Nikolaevich Grigorovich is an outstanding Russian choreographer of the 20th century. Yury Nikolaevich Grigorovich is an outstanding Russian choreographer of the 20th century.

Grigorovich was the soloist of the Maryinsky Theatre for 18 years and later for a short time headed its ballet. His first productions at the Kirov were 'The Stone Flower' and 'The Legend of Love'. They marked the birth of a new choreographer soon to be known all over the world and of a new trend that many years determined the development of ballet in Russia.

Since 1964 and for over 30 years Grigorovich has been the choreographer-in-chief of the Bolshoy Theatre. It was the time of the greatest achievements in the artistic activity of the company, when it won the world acknowledgment and authority. The Bolshoy Theatre with Grigorovich at the head made international tours over than 90 times. He established the leadership of Russian Classic Ballet everywhere in the world and brought to the world stage brilliant dancers.

In Moscow Yury Grigorovich created ballets which won the world-wide reputation, among them 'The Nutcracker' (1966), 'Spartacus' (1968), 'Ivan the Terrible' (1975), 'Angara' (1976), 'Romeo and Juliet', 'The Golden Age' (1982). He also choreographed new versions of such masterpieces of the past as: 'The Sleeping Beauty' (1963, 1973) and 'Swan Lake', 'Raymonda' (1984), 'La Bayadere' (1991) and 'Don Quixote', 'Giselle' (1987) and 'Le Corsaire' (1994).

According to the Russian critic Poel Karp, 'Grigorovich kept to the type of Petipa's 'grand ballet', but he wanted his ballets to the strongly built dramatically and have unity of style. Thus he created a new genre 'Grigorovich's grand ballet'.

Yuri Grigorovich staged his ballets in Stockholm, Rome, Paris, Copenhagen, Vienna, Milano, Ankara, Prague, Sofia, Genoa, Warsaw.

In 1990-1994 he founded the new company 'Grigorovich-Ballet'. In 1996 he choreographed for different companies from Ufa, Krasnodar and Omsk.

The ballets of Russian master Yury Grigorovich dominate the repertoire of contemporary works. His stagings of the classic ballets reflect his conviction that drama must always infuse dance. Born in Leningrad in 1927, he trained at the Leningrad Choreographic School. He joined the Kirov Ballet, where he excelled in many roles including virtuoso warrior leader Nurali in The Fountain of Bakhchisarai. He was named the ballet master at the Kirov in 1962, but subsequently transferred to the Bolshoi in 1964, where he would stay for 30 years. That tenure is rivaled only by the founding director of the New York City Ballet, George Balanchine.

For a long period Yury Grigorovich has been heading juries of many international competitions. Grigorovich was rewarded with the highest staterecompenses, honorary titles and international prizes for his merits. He is a Member of Vienna Music Society, Honorable Chairman of International Theatre Institute, Chairman of International Choreography Association and Honorable Chairman of the Ukrainian Dance Academy.

Gubaidulina S.

Sofia Gubaidulina was born in Chistopol in the Tatar Republic of the Soviet Union in 1931. After instruction in piano and composition at the Kazan Conservatory, she studied composition with Nikolai Peiko at the Moscow Conservatory, pursuing graduate studies there under Vissarion Shebalin. Until 1992, she lived in Moscow. Since then, she has made her primary residence in Germany, outside Hamburg.

Gubaidulina's compositional interests have been stimulated by the tactile exploration and improvisation with rare Russian, Caucasian, and Asian folk and ritual instruments collected by the "Astreia" ensemble, of which she was a co-founder, by the rapid absorption and personalization of contemporary Western musical techniques (a characteristic, too, of other Soviet composers of the post-Stalin generation including Edison Denisov and Alfred Schnittke), and by a deep-rooted belief in the mystical properties of music.

Her uncompromising dedication to a singular vision did not endear her to the Soviet musical establishment, but her music was championed in Russia by a number of devoted performers including Vladimir Tonkha, Friedrich Lips, Mark Pekarsky, and Valery Popov. The determined advocacy of Gidon Kremer, dedicatee of Gubaidulina's masterly violin concerto, Offertorium, helped bring the composer to international attention in the early 1980s. Gubaidulina is the author of symphonic and choral works, two cello concerti, a viola concerto, four string quartets, a string trio, works for percussion ensemble, and many works for nonstandard instruments and distinctive combinations of instruments. Her scores frequently explore unconventional techniques of sound production.

Since 1985, when she was first allowed to travel to the West, Gubaidulina's stature in the world of contemporary music has skyrocketed. She has been the recipient of prestigious commissions from the Berlin, Helsinki, and Holland Festivals, the Library of Congress, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, and many other organizations and ensembles. The major triumph of the recent past was the premiere in 2002 of the monumental two-part cycle, Passion and Resurrection of Jesus Christ according to St. John, commissioned respectively by the International Bachakademie Stuttgart and the Norddeutschen Rundfunk, Hamburg.

Gubaidulina made her first visit to North America in 1987 as a guest of Louisville's "Sound Celebration." She has returned many times since as a featured composer of festivals ? Boston's "Making Music Together" (1988), Vancouver's "New Music" (1991), Tanglewood (1997) ? and for other performance milestones. From the retrospective concert by Continuum (New York, 1989) to the world premieres of commissioned works ? Pro et Contra by the Louisville Orchestra (1989), String Quartet No. 4 by the Kronos Quartet (New York, 1994), Dancer on a Tightrope by Robert Mann and Ursula Oppens (Washington, DC, 1994), the Viola Concerto by Yuri Bashmet with the Chicago Symphony conducted by Kent Nagano (1997), and Two Paths ("A Dedication to Mary and Martha") for two solo violas and orchestra, by the New York Philharmonic conducted by Kurt Masur (1999) ? the accolades of American critics have been ecstatic. Eagerly anticipated are premieres of orchestral works commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra (2003), and a joint commission by the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (2006).

Gubaidulina is a member of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin and the Freie Akademie der Künste in Hamburg. She has been the recipient of the Prix de Monaco (1987), the Premio Franco Abbiato (1991), the Heidelberger Künstlerinnenpreis (1991), the Russian State Prize (1992), and the SpohrPreis (1995). Her most recent awards include the prestigious Praemium Imperiale in Japan (1998), the Sonning Prize in Denmark (1999), and the Polar Music Prize in Sweden (2002).

Her music is now represented on compact disc generously; Gubaidulina has been honored twice with the coveted Koussevitzky International Recording Award. Major releases have appeared on the DG, Chandos, Philips, Sony Classical, BIS, and Berlin Classics labels.

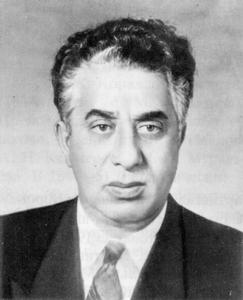

Khachaturyan A. I.

Aram Ilyich Khacaturyan (1903 - 1978) Aram Ilyich Khacaturyan (1903 - 1978)

A central figure in the history of Soviet music, Khachaturyan composed some of the best-loved and most accessible music to come out of Soviet Russia. His career spanned almost the entire period of Communist rule: he began his studies five years after the establishment of the Soviet Union and died twelve years before its eventual collapse. As with all successful Soviet composers, he managed to tread a fine line between kowtowing to the demands of the state and producing music of high enough quality to earn critical acclaim and gain a popular following.

Khachaturian was one of the "Big Three", as the leading composers of the Soviet Union were known. Along with the other two, Shostakovich and Prokofiev, he was the only Soviet composer to succeed in making a substantial name for himself on an international level. Though the three men are often bracketed together, the similarities linking their music are little more than superficial.

Born in Tbilisi, the capital of the ancient Caucasian nation of Georgia, Khachaturyan was descended from a working-class family of Armenian origin. His father, a bookbinder, gave no special encouragement to his son's musical skills. Instead, he provided a traditional upbringing in which the folk music of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan provided a rich backdrop to many social occasions. Khachaturian learned the tenor horn and piano at school, but not until he moved to Moscow in 1921 was his exceptional talent was discovered.

The overwhelming musical influence on Khachaturyan during his formative years was the folk music that surrounded him. This influence proved vital to the creation of the musical language which he developed over many years of study in Moscow. Earlier Russian composers, particularly Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin, had used pseudo-Oriental melodies to invoke the atmosphere of the lands east and south of Russia. These tunes were far from authentic, bearing only a passing resemblance to their models.

Khachaturian, on the other hand, spent his youth surrounded by just the sort of Asiatic melodies and rhythms that these composers had attempted to emulate. As a result his music provides a far more convincing evocation of the folk music of the Caucasus than that of any other composer of his stature. Vivid, temperamental and deeply emotional, it is clothed in rich and sensuous orchestral textures. A particular feature of his music is the frequent and prominent use of tuned percussion instruments, in particular the xylophone.

In addition to his grounding in folk music, Khachaturian assimilated elements of the music of Ravel and Gershwin during his training. From Ravel he derived his shimmering orchestration and rich, shifting harmonies; Gershwin provided a model for his more jazz-inflected and percussive scores. He also picked up a rigorous compositional discipline from the teachings of Rimsky-Korsakov.

A sworn enemy of modernism, Khachaturian is at his best when providing a musical counterpart to pictorial or dramatic subjects. His music for ballet and theatre contains much of his best-loved creations. The demonic Sabre Dance from Gayaneh is justly famous, while the suites from Masquerade and Spartacus are among his most often-performed works. He also produced over 25 highly accomplished film scores.

Markevitch I.

Igor Markevitch was born in Kiev July 27, 1912. His father, Boris Markevitch, was a pianist and studied with the famous Eugene d'Albert. The Name of Igor's mother was Zola Pokitnova. In 1914 the Markevitch family fled to Paris. But there they did not stay for a long time. Two years later they setteled in La-Tour-de-Peilz (Vevey), Switzerland. Igor Markevitch was born in Kiev July 27, 1912. His father, Boris Markevitch, was a pianist and studied with the famous Eugene d'Albert. The Name of Igor's mother was Zola Pokitnova. In 1914 the Markevitch family fled to Paris. But there they did not stay for a long time. Two years later they setteled in La-Tour-de-Peilz (Vevey), Switzerland.

Most of the time Igor Markevitch spoke French, and the titles of his works are normally in French. Until 1923, when his father died, Igor studied piano with him. At the age of 13 Igor Markevitch played his piano suite "Noces" to Alfred Cortot. Cortot was very much impressed and invited Markevitch to study with him. In addition to this, Markevitch studied at the "École Normale de Musique" in Paris from 1926 to 1928. Here Nadia Boulanger teached him harmony and counterpoint. In 1929 he completed his diplomas at the "École Normale".

When listening to "Noces" Alfred Cortot was very much impressed - this time it's Dyagilev, who is faszinated by this work. After listening to "Noces" and the "Sinfonietta", he commissions two new works from Markevitch: a "Piano Concerto" and "L'Habit du Roi" [The Emperor's New Clothes], a ballet with scenario by Boris Kochno and designes by Picasso. But on August 19, 1929 Dyagilev died and the ballet music is abandoned - just some of its music is incorporated into "Cantata" with a new text written by Jean Cocteau.

In the following years Markevitch's compositions are getting more and more famous. The "Piano Concerto", "Cantata", "Concerto Grosso" and "Rébus" get very successful premières in Europe and the US. They get performances by conductors like Désormière, Rosbaud, Monteux and Koussevitzky. One of the most successful performances must have been the première of "L'Envol d'Icare" [The Flight of Icarus] on June 26, 1933 with Désormière as conductor. This work plays an important role in the life of Igor Markevitch. Darius Milhaud said about it: "this work... will probably mark a date in the evolution of music".

Now Markevitch is at the peak of success. He is called the "Second Igor" by many people who compare him to Igor Stravinsky [Stravinsky himself doesn't like this comparison and Markevitch is now 'persona non grata' with Stravinsky]. But despite of Markevitch's growing fame as a composer now he starts to develop in another direction. From 1934 Markevitch studies occasionally conducting with Hermann Scherchen in Switzerland. On December 20 1935 he replaces Scherchen in conducting the première of Markevitch's oratorio "Le Paradis perdu" [Paradise Lost] at Queen's Hall in London.

In April 1936 Markevitch and Kyra, the daughtor of Vaslav Nijinsky, get married. They live together in Corsier, Switzerland. The marriage lasts nine years, but they live estranged after four years. Their son Vaclav was named after his grandfather Vaslav Nijinsky.

In the following years Markevitch composes a lot and his works are well received by the critics and the public, especially the performance of "L'Envol d'Icare" at the Biennale in Venice in 1937 and the première of "Le Nouvel Âge" in Warsaw in 1938. Nevertheless these are hard times for Markevitch. The Second World War is approaching, the conditions in Europe get worse. He supplements his income by giving lectures, piano recitals and radio broadcasts in Switzerland and abroad. In 1940 he visits Florence together with his wife Kyra. Here he composes "Lorenzo Il Magnifico", a "vocal symphony". Markevitch stays in Italy, where Kyra now teaches dance, after he has failed to comply with Swiss residency laws. He is now technically stateless. The couple lives in Settignano and Markevitch falls seriously ill after a hard winter in 1941/42. This is the major crisis in his life. Later he will say that he felt "dead between two lives". After his illness he never composed again - his last composition is from 1941. At this time Markevitch is just 29 years old.

What happened? Well, it's hard if not impossible to give a satisfying answer to this question. For sure Markevitch is deeply affected by the horrors of the Second World War [by that time the war already spreaded to Italy]. His psychological crisis probably influences his physical health, too and results in his serious illness. But this is just speculation. Even if we look at Markevitch's autobiography "Être et avoir été" from 1980 we can't find an answer. It's only sure that he almost denied the existence of his own music until nearly seventy years old. When questioned about his "first life" as a composer he replied in 1958:

"I would say to you, very frankly, that I am objective enough to claim that there is music which needs to be heard before mine, and for which the need is more urgent. Apart from that, if my works are good enough, they can wait; and if they cannot wait, it is pointless to play them."

Despite Markevitch's own critical comments on his music, I think that it is really worth to get rediscovered. Markevitch himself changed his attitude towards his music in 1978 when he conducted "L'Envol d'Icare" and "Le Paradis perdu" in Brussels. The time between the crisis and 1978 was a time of great success for Markevitch, but it was the success of the conductor, not the composer. So it's not that important for us in this context.

In 1943 Markevitch joins the Partisans in their fight against Fascism, becoming a member of the Committee of Liberation of the Italian Resistance and in 1947 he is naturalised as an Italian citizen. After getting a divorce from Kyra he marries Topazia Caetani. Markevitch is travelling a lot at this time. His international conducting career takes him to music directorships in Stockholm, Paris, Montreal, Madrid, Monte Carlo, Havana and Rome.

More than 30 years later, in 1978, Markevitch conducts "L'Envol d'Icare" and "Le Paradis perdu" in Brussels. Both concerts are successful and "Boosey & Hawkes" in London offer him a publication contract. But this doesn't result in recordings of Markevitch's works. Until today there are just a few CDs available [I only know about the Marco Polo series and the Largo CD]. In addition to these CDs there are only a few works which are preserved from 1930's radio broadcasts, and a recording on 78s of "L'Envol d'Icare" from 1938.

Markevitch's autobiography "Être et avoir été" [Beeing and having been] is published by Gallimard in 1980. The same year he undertakes revision of some of his works from the 1930s. Three years later Markevitch travels to Kiev, his city of birth - in this year, 1983, he suddenly falls ill and dies in Antibes on 7th March.

Mussorgsky M. P.

Mussorgsky, Modest Petrovich (1839 - 1881)

Mussorgsky was one of the five Russian nationalist composers, roughly grouped under the influence of the unreliable Balakirev. Initially an army officer and later, intermittently, a civil servant, Mussorgsky left much unfinished at his death in 1881, nevertheless his influence on composers such as Janácek was considerable, not least in the association he found between speech intonations and rhythms and melody. Rimsky-Korsakov, a musician who had acquired a more conventional technique of orchestration and composition, revised and completed a number of Mussorgsky's works, versions which now may seem inferior to the innovative original compositions as Mussorgsky conceived them.

The greatest of Mussorgsky's creations was the opera Boris Godunov, based on Pushkin and Karamazin, with a thoroughly Russian historical subject. He completed the first version in 1869 and a second version in the 1870s, but it was Rimsky-Korsakov's version that was first performed outside Russia. The opera provides an important part for a bass in the rôle of Boris. Other operas by Mussorgsky include Khovanshchina, completed and orchestrated by Rimsky-Korsakov. A later version by Shostakovich restores more of the original text. The opera Sorochintsy Fair, after Gogol, completed by Lyadov and others, includes the orchestral favourite Night on the Bare Mountain, an orchestral witches' sabbath.

Mussorgsky's 1874 suite Pictures at an Exhibition, a tribute to the versatile artist Hartman, has proved the most popular of all the composer's works, both in its original version for piano and in colourful orchestral versions, of which that by Maurice Ravel has proved the most generally acceptable. Linked by Promenades for the visitor to the exhibition, Mussorgsky represents in music a varied collection, from the Market of Limoges and the Catacombs to the final Great Gate of Kiev, a monumental translation into music of an architectural design for a triumphal gateway.

Mussorgsky wrote a number of choral works and songs, many of the latter of considerable interest, including the group The Nursery. The Song of the Flea, based on Goethe's Mephistophelean song in Faust, is a bass favourite.

Prokofiev S. S.

Born on 23-April-1891 (11-April-1891 old style) in Sontsovka, Ukraine, Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev is considered one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century. Born on 23-April-1891 (11-April-1891 old style) in Sontsovka, Ukraine, Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev is considered one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century.

His father Sergei Alexeyevich Prokofiev was an agricultural engineer, and his mother Maria Grigoryevna Prokofieva (born Zhitkova) was a well-educated woman with a keen musical sense and piano skills to match. His mother became the highly gifted child's first mentor in music and arranged trips to the opera in Moscow. A high evaluation was put upon the boy's talent by a Moscow composer and teacher, Sergey Taneyev, on whose recommendation the Russian composer Reinhold Glier twice went to Sontsovka in the summer months to become young Sergey's first teacher in theory and composition and to prepare him for entrance into the conservatory at St. Petersburg. The years Prokofiev spent there--1904 to 1914--were a period of swift creative growth. His teachers were struck by the originality of his musical thinking. When he graduated he was awarded the Anton Rubinstein Prize in piano for a brilliant performance of his own first large-scale work--the Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Flat Major, Opus 10.

The conservatory gave Prokofiev a firm foundation in the academic fundamentals of music, but he avidly sought musical innovation. His enthusiasms were supported by progressive circles advocating musical renewal. Prokofiev's first public appearance as a pianist took place before such a group in St. Petersburg in 1908. A little later he met with friendly sympathy in a similar circle in Moscow, which helped him make his first appearances as a composer, at the Moscow summer symphony seasons of 1911 and 1912.

Prokofiev's talent developed rapidly as he applied many new musical ideas. He studied the compositions of Igor Stravinsky, particularly the early ballets, but maintained a critical attitude toward his countryman's brilliant innovations. Contacts with the then new currents in theatre, poetry, and painting also played an important role in Prokofiev's development. He was attracted by the work of modernist Russian poets; by the painting of the Russian followers of Cézanne and Picasso; and by the theatrical ideas of Vsevolod Meyerhold, whose experimental productions were directed against an obsolescent naturalism. In 1914 Prokofiev became acquainted with the great ballet impresario Sergey Diaghilev, who became one of his most influential advisers for the next decade and a half.

After the death of his father in 1910, Prokofiev lived under more straitened material conditions, though his mother provided for his continuing studies. On the eve of World War I, he visited London and Paris to acquaint himself with the newest in art. The tense pre-storm atmosphere that pervaded Russia sharpened in him a feeling of skepticism, of disbelief in romantic ideals, but did not shake his essentially healthy outlook on life. Exempt from war mobilization as the only son of a widow, Prokofiev continued to perfect his musicianship on the organ and appeared in concerts in the capital and elsewhere. The pre-Revolutionary period of Prokofiev's work was marked by intense exploration. The harmonic thought and design of his work grew more and more complicated. Prokofiev wrote the ballet Ala and Lolli (1914), on themes of ancient Slav mythology, for Diaghilev, who rejected it. Thereupon, Prokofiev reworked the music into the Scythian Suite, Opus 20, for orchestra. Its premiere in 1916 caused a scandal but was the culmination of his career in Petrograd. The ballet The Tale of the Buffoon Who Outjested Seven Buffoons (1915; The Buffoon, 1915-20), also commissioned by Diaghilev, was based on a folktale; it served as a stimulus for Prokofiev's searching experiments in the renewal of Russian music.

The next decade and a half are commonly called the foreign period of Prokofiev's work. For a number of reasons, chiefly the continued blockade of the Soviet Union, he could not return at once to his homeland. Nevertheless, he did not lose touch with Russia. The first five years of Prokofiev's life abroad are usually characterized as the "years of wandering." On the way from Vladivostok to San Francisco, in the summer of 1918, he gave several concerts in Tokyo and Yokohama. In New York City the sensational piano recitals of the "Bolshevik Pianist" evoked both delight and denunciation. The composer had entrée to the Chicago Opera Association, where he was given a commission for a comic opera. The conductor and the producer of the opera, both Italian, gladly backed the idea of an opera on the Gozzi plot. Accordingly, The Love for Three Oranges was completed in 1919, though it was not produced until 1921. Within a few years the opera was also produced with immense success on the stages of the Soviet Union as well as in western Europe.

In America, Prokofiev met a young singer of Spanish extraction, Lina Llubera, who eventually became his first wife and the mother of two of his sons, Svyatoslav and Oleg. From the first days of the war, the composer's attention was centred on a very large-scale operatic project: an opera based on Leo Tolstoy's novel War and Peace. He was fascinated by the parallels between 1812, when Russia crushed Napoleon's invasion, and the then-current situation. The first version of the opera was completed by the summer of 1942, but subsequently the work was fundamentally revised, a task that occupied more than 10 years of intensive work. Those who heard it were struck both by the immense scale of the opera (13 scenes, more than 60 characters) and by its unique blend of epic narrative with lyrical scenes depicting the personal destinies of the major characters. An increasing predilection for national-epical imagery is manifested in the heroic majesty of the Symphony No. 5 in B Flat Major (1944) and in the music (composed 1942-45) for Eisenstein's two-part film Ivan the Terrible (Part I, 1944; Part II, 1948). Living in the Caucasus, in central Asia, and in the Urals, the composer was everywhere interested in the folklore, an interest that was reflected in the String Quartet No. 2 in F Major, on Kabardinian and Balkarian themes (1941), and in the comic opera Khan Buzai, on themes of Kazakh folktales. Documents of those troubled days are three piano sonatas, No. 6 (1940), No. 7 (1942), and No. 8 (1944), which are striking in the dramatic conflict of their images and in their irrepressible dynamism.

Overwork was fatal to the composer's health. During the last years of his life, Prokofiev seldom left his villa in a suburb of Moscow. His propensity for innovation, however, is still evident in such important works as the Symphony No. 6 in E Flat Minor (1945-47), which is laden with reminiscence of the tragedies of the war just past; the Sinfonia Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in E Minor (1950-52), composed with consultation from the conductor and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich; and the Violin Sonata in F Minor (1938-46), dedicated to the violinist David Oistrakh, which is in Russian folk imagery. Just as in earlier years, the composer devoted the greatest part of his energy to musical theatre: cases in point were the opera The Story of a Real Man (1947-48), the ballet The Stone Flower (1948-50), and the oratorio On Guard for Peace (1950). The lyrical Symphony No. 7 in C Sharp Minor (1951-52) was the composer's swan song.

In 1953 Prokofiev died suddenly of cerebral hemorrhage. On his worktable there remained a pile of unfinished compositions, including sketches for a 6th concerto for two pianos, a 10th and an 11th piano sonata, a Kazakh comic opera, and a solo violoncello sonata. The subsequent years saw a rapid growth of his popularity in the Soviet Union and abroad. In 1957 he was posthumously awarded the Soviet Union's highest honour, the Lenin Prize, for the Seventh Symphony.

Rakhmaninov S. V.

Sergey Vasiliyevich Rakhmaninov Sergey Vasiliyevich Rakhmaninov

He was born 1 April 1873 in Novorodsky region.

Composer, conductor and pianist.

He studied at the Moscow Conservatory (1885-92) under Zverev (where Skryabin was a fellow pupil) and his cousin Ziloti for piano and Taneyev and Arensky for composition, graduating with distinction as both pianist and composer (the opera Aleko, given at the Bolshoy in 1893, was his diploma piece). During the ensuing years he composed piano pieces (including his famous C# minor Prelude), songs and orchestral works, but the disastrous première in 1897 of his Symphony no. 1 poorly conducted by Glazunov, brought about a creative despair that was not dispelled until he sought medical help in 1900: then he quickly composed his Second Piano Concerto. Meanwhile he had set out on a new career as a conductor, appearing in Moscow and London; he later was conductor at the Bolshoy, 1904-6.

By this stage, and most particularly in the Piano Concerto no. 2, the essentials of his art had been assembled: the command of the emotional gesture conceived as lyrical melody extended from small motifs, the concealment behind this of subtleties in orchestration and structure, the broad sweep of his lines and forms, the predominant melancholy and nostalgia, the loyalty to the finer Russian Romanticism inherited from Tchaikovsky and his teachers. These things were not to change, and during the remaining years to the Revolution they provided him with the materials for a sizable output of operas liturgical music, orchestral works, piano pieces and songs, even though composition was generally restricted to periods of seclusion between concert engagements. In 1909 he made his first American tour as a pianist, for which he wrote the Piano Concerto no. 3.

Soon after the October Revolution he left Russia with his family for Scandinavia; in 1918 they arrived in New York, where he mainly lived thereafter, though he spent periods in Paris (where he founded a publishing firm), Dresden and Switzerland. There was a period of creative silence until 1926 when he wrote the Piano Concerto no. 4, followed by only a handful of works over the next 15 years, even though all are on a large scale. During this period, however, he was active as a pianist on both sides of the Atlantic (though never again in Russia). As a pianist he was famous for his precision, rhythmic drive, legato and clarity of texture and for the broad design of his performances.

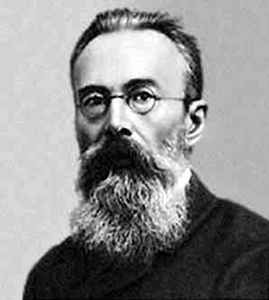

Rimsky-Korsakov N. A.

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (1884 - 1908) Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (1884 - 1908)

Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov was born in a small provincial town called Tikhvin , 200 km from St.Petersburg.

His family was unusual by the age of its members. At the time of his birth his father was 60, his mother 42 and his brother was already a naval officer and was 22 years old.

In Tikhvin little Nika learned to play the piano. His parents noticed, that he made good progress and had a perfect ear. But they did not pay attention to this. At his parents will, Nika, when he was twelve, entered the Naval School at St.Petersburg to become a mariner following his brother.

From that time he began to go to operas, symphonic concerts and acquired a passion for music. His new music teacher Canille noticed the musical gift of his pupil and told him he should try to compose music himself. Canille explained the general rules of musical composition, set him homework and soon introduced to the composer Mily Balakirev who was the head of a St.Petersburg musical circle. During the last year of his studies at the Naval School (1861/62) Nikolay began to compose a symphony. He was happy and dreamed to become a composer.

But his mother and brother (his father died in March 1862) convinced him that a musical career would not ensure a sufficient income, and therefore he should become a naval officer. In order to do this, he had to embark on a round-the-world trip. In October 1862 Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov set off from Kronstadt as a gardemarine on the clipper "Almaz".

The young composer agreed with his parents hoping he would be able to compose on the ship. But the atmosphere there was not suitable to write musical compositions. Official duties did not allow any spare time for music. There was no piano or any other musical instrument on the ship. Not one of the crew took any interest in music. Nevertheless, during the first months of the cruise, mainly during a long stop in England (winter 1862/63) he composed the Andante for his symphony. But later, little by little, his passion for music died down. He thought that music was no longer a part of his life. The cruise lasted 2 years and 8 months. During this time Rimsky- Korsakov visited Germany, England, The United States of America (where he went on a trip to the Niagara Falls), Brazil, France and Spain. He saw many different aspects of nature, particularly of the Northern, Equatorial and Southern seas, the stormy and calm ocean, the starry sky of the Southern hemisphere.

All these natural pictures left striking impressions in his memory. Later he interpreted in his music, with a great talent,these impressions, as well as the natural phenomenon of the North of Russia. He created beautiful musical pictures of the sea (e.g. in "Sadko", "The Tale of the Tsar Saltan", "Sheherazade"); of the forest with its sounds (e.g. in "The Snowmaiden", "The Legend of the Invisible Town Kitez"); of the air and sky (e.g. in "The Christmas Night", "Kashtshey Immortal").

After Rimsky-Korsakov came back to Russia (May,1865), he began to work for the Coast Service in St.Petersburg and intended to enter the Naval Academy. But in St.Petersburg he met his former musical friends, who forced him to return to music and to complete his symphony. In the same year, on December 19th , the N.Rimsky-Korsakov's first symphony was performed for the first time in a concert with Mily Balakirev as the conductor, and it was a great success. The audience were astonished, when they saw that the author was a very young naval officer. So his musical career began. Still he had to earn a living and thus only gave up active naval service eight years later.

Rimsky-Korsakov's musical activity did not only include the creative work. From 1871, when he was twenty seven, and until the end of his life, he was a professor of the St.Petersburg Conservatoire; he held a civilian post of the inspector of the Naval Brass-bands for ten years (1873-1883); worked as the Director of the Free Music School for seven years (1874-1881); was the Director' s Assistant of the Imperial Capella for ten years (1883-1893); conducted symphonic concerts for more than thirty years (1874-1907) at St.Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, Brussels and Paris. He died in his own country-seat, Loubensk when he was sixty four.

Shostakovich D. D.

Dmitry Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, born in Saint Petersburg, Sept. 25 (N.S.), 1906, d. Aug. 9, 1975, was one of the foremost 20th-century Soviet composers. He showed no bent for music until age nine, when he started lessons with his mother, a piano teacher. In scarcely a month he was playing simple classics and trying to compose, and at 11, he performed Bach's entire Well-Tempered Clavier. Accepted into the Petrograd Conservatory in 1919, he studied piano with Leonid Nikolaev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. The sensational premiere in 1926 of his First Symphony and its subsequent successes abroad identified him as the leading young composer in Russia after the Revolutions of 1917. Dmitry Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, born in Saint Petersburg, Sept. 25 (N.S.), 1906, d. Aug. 9, 1975, was one of the foremost 20th-century Soviet composers. He showed no bent for music until age nine, when he started lessons with his mother, a piano teacher. In scarcely a month he was playing simple classics and trying to compose, and at 11, he performed Bach's entire Well-Tempered Clavier. Accepted into the Petrograd Conservatory in 1919, he studied piano with Leonid Nikolaev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. The sensational premiere in 1926 of his First Symphony and its subsequent successes abroad identified him as the leading young composer in Russia after the Revolutions of 1917.

Drawn into a semiofficial role as representative of Soviet music, Shostakovich's career evolved in the constant glare of publicity. He responded by composing many works of a topical character, among them 4 of his 15 symphonies--the 2d, To October (1927), the 3d, May First (1929), the 11th, The Year 1905 (1957), and the 12th, The Year 1917 (1961).

An interest in modernist devices, love of irony (both in choice of subject and its treatment), and commitment to personal creative vision brought him repeatedly into the center of controversy. His opera The Nose, produced in Leningrad in 1930, was withdrawn under attack for its "bourgeois decadence." In 1936, Pravda declared Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, another of his operas, "a mess instead of music." He was chastised along with Sergei Prokofiev in 1948 for "formalistic excesses" counter to the spirit of Socialist realism. His Thirteenth Symphony (1962), which memorialized the Jews massacred by the Nazis at Babi-Yar during World War II, angered Communist officials by implicitly criticizing residual Soviet anti-Semitism.

Following Prokofiev's death in 1953 and his own admission into the Communist party in 1960, Shostakovich was widely acclaimed the foremost Soviet composer--a position still unchallenged at the time of his death. His musical language remained rooted in tonality, despite free dissonance, intricate counterpoint, and even transient dodecaphony (12-tone style). A refined eclecticism and flair for musical satire survived even the dark subjectivism of his last works, as in the references to Rossini's William Tell overture and Wagner's Ring and Tristan in his Fifteenth Symphony (1971). His autobiography, Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich, was published in 1979, but the authenticity of the work was disputed by Soviet officialdom. His son Maxim Shostakovich, b. May 10, 1939, a pianist and conductor of the Moscow Central Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra, decided to stay in the West while visiting Europe in 1981.

Slonimsky S.

Slonimsky was born in 1932 in Leningrad, studied composition under Shebalin, Evlakhov, polyphony - under Nicolai Uspensky, the author of the reading book "Samples of Ancient Russian Vocal Art", piano - under Artobolevskaya, Savshinsky, Nilsen.

The modern Russian composer, professor of St. Peterburg conservatoire named after Rimsky-Korsakov and Samara Pedagogical University, Winner of the Glinca state Prize and of the St. Petersburg Government Prize, Academician of the Russian Academy of Education, the People's Artist of Russia. He was born in 1932 in Leningrad, studied composition under Shebalin, Evlakhov, polyphony - under Nicolai Uspensky, the author of the reading book "Samples of Ancient Russian Vocal Art", piano - under Artobolevskaya, Savshinsky, Nilsen.

The composer's father was a Russian writer and an active member of the literary circle "The Serapion Brothers" - Mikhail Slonimsky (1897-1972); his uncle Nicolai Slonimsky (1894-1995) was a famous American musical expert, the author of fundamental musical encyclopedias; his father's cousin Anthony Slonimsky (1895-1976) was a famous Polish poet and political dissident.

Sergey Slonimsky is the author of such operas as "Virinea" (1967), "The master and Margarita" (1972), "Mary Stuart" (1980), "Hamlet" (1990), "Tsar Ixion" (1993), "Ioann the Terrible's vision" (1995); of ten symphonies (The Tenth - "Circles of Hell" after Dante - recorded on CD in Russia), the ballet "Icarus".

"Virinea" was staged in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Samara, Perm; his opera "The Master and Margarita (chronologically the first adaptation for stage of Bulgakov's novel) had been prohibited for stage during seventeen years after the performance of the first act in the Leningrad House of Composers conducted by Gennady Rozhdestvensky. "Mary Stuart" was staged in Samara, St. Petersburg, Leipzig, Olomouts, Alma-Ata. Dramma per musica "Hamlet" is on in Samara and Krasnoyarsk. The ballet "Icarus" was shown in Bolshoi Theatre, on the stage of the Kremlin Palace of Congress (choreographer and performer - Vladimir Vassiliev), in the Mariimsky Theatre of St. Petersburg (choreographer Igor Belsky) and in Brno (choreographer Daniel Visner).

Sergei Slonimsky the author of more than a hundred compositions, among them - Concerto-Buffo (performed several times in the USA and England conducted by Yuri Temirkanov), Organ, Violin, Oboe, Balalaika, Electric Guitar Concerts, recently finished Piano Concert ("Jewish Rhapsody"), Cello Concert, 24 preludes and fuges, which are played in Russia and abroad and are in the pedagogical and concert repertoire of pianists.

Theatre and symphony opuses of the composer were perfomed by such famous conductors as Kondrashin, Yansons, Grikurov, Rozhdestvensky, Chernushenko, Sinaisky, Simonov, Ermler, Chistyakov, Talmi, Krents, Class, Sondetskis, Dalgat, Nesterov, Provatorov, Kovalenko, Shcherbakov and many others.

One of the new compositions by Slonimsky is "Petersburg's Visions" after Dostoevsky was perfomed by Yuri Temirkanov in eight cities of the USA, including New York (Carnegi Hall), Boston, San-Fransisco, Los-Angeles in 1996.